Welcome to the realm of hacktivism, where technology meets activism. Verifying and investigating hacktivist claims is often a challenging, time-consuming task. The sheer volume of assertions made by various hacktivist groups and individuals can be overwhelming, especially when multiple events unfold simultaneously. This environment can strain resources needed for thorough fact-checking.

Hacktivist activities often include digital intrusions like website defacements or data breaches. These actions may leave limited forensic evidence, and when they do, such artifacts are typically short-lived and rarely accessible for independent analysis. Verifying Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks is even more complex, as third-party verification is difficult without access to the targeted site’s logs. This lack of transparency complicates efforts to confirm the authenticity and extent of hacktivist actions.

The challenges of quickly validating or debunking these claims allow misinformation to circulate unchecked. By the time accurate information surfaces, the initial narrative may have already gained momentum, leading to confusion, distrust, and a distorted understanding of online activism’s actual impact.

UK NCSC warning

In April 2023, the UK National Cyber Security Center (NCSC) issued an alert over “a new class of Russian cyber adversary” that has emerged. These adversaries are often not under “formal state control” and often focus on DDoS attacks, website defacements, and/or the spread of misinformation in support of the Russian invasion or Russia’s perceived interests. The NCSC also warned that some desire to achieve a more disruptive and destructive impact against western critical national infrastructure (CNI), including the UK.

Due to the UK NCSC’s warning, alongside advisories from other authorities, monitoring these unpredictable cyber nuisances is still ongoing for many cyber threat intelligence (CTI) teams. However, these adversaries are hard to take seriously due to some of the examples and case studies shared in this blog.

Omg! Cyber Cat hacked the UK Hydrographic Office!!

Around 11am on 27 July 2023, the UK Hydrographic Office tweeted that they were investigating reported rumours of a cyber incident. Before 4pm that same day, the UK Hydrographic Office tweeted again that there was no indications of a breach or compromise. So what happened?

Earlier that day, one of these pro-Russian hacktivist groups that call themselves “Cyber Cat” shared to their public Telegram channel that they had compromised the UK Hydrographic Office using “social engineering” and had taken control of their server. They also attempted to ransom the UK Hydrographic Office for “2BTC” for the data (approx. £45,000). This message was promptly amplified by an affiliated hacktivist group’s Telegram channel called “Net Worker Alliance”.

Figure 1: UK Hydrographic Office allegedly “compromised” by Cyber Cat

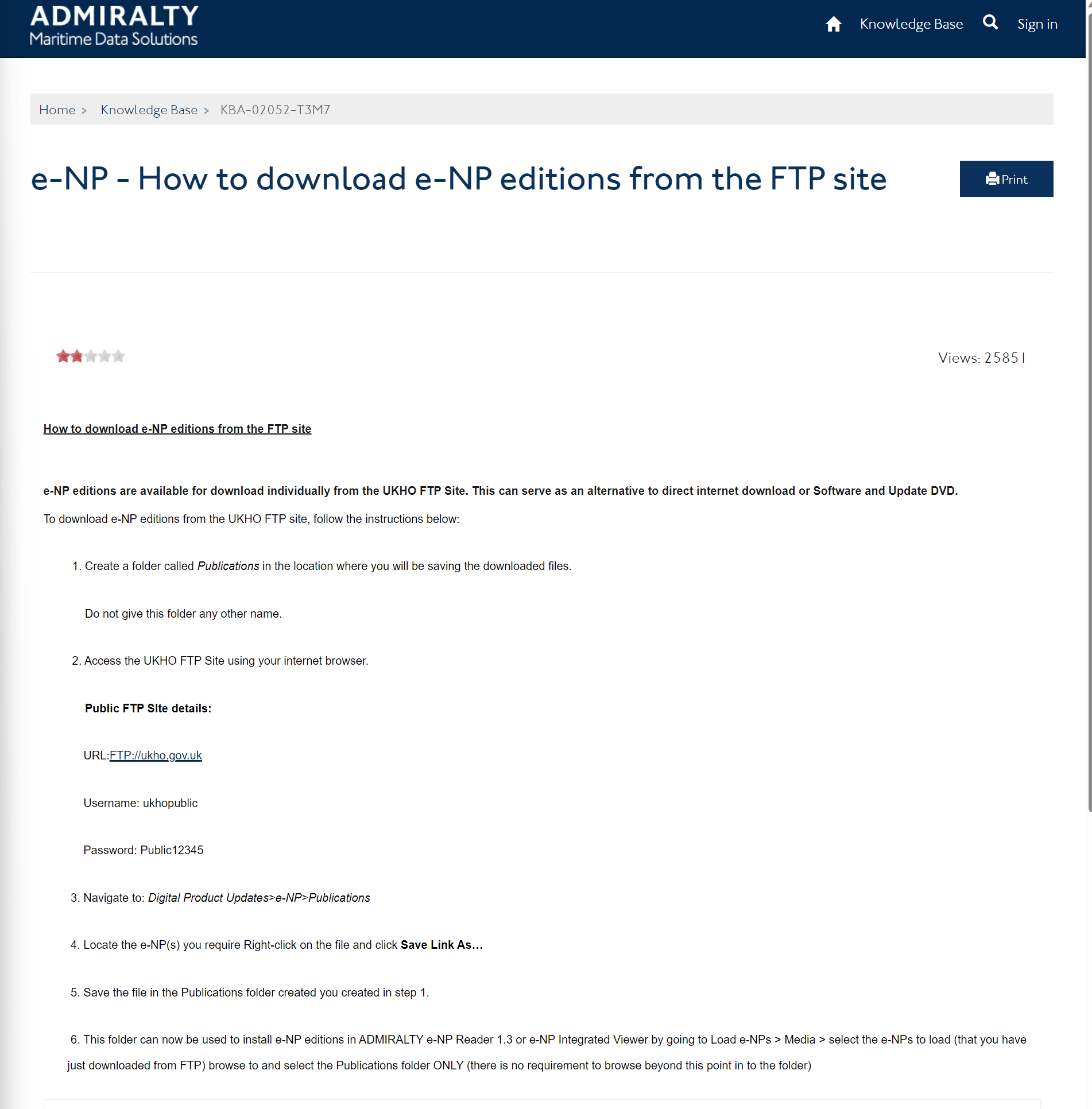

However, security researcher @UK_Daniel_Card managed to correctly identify that this was not a hack or compromise or anything of the sort. All the Cyber Cat had done was go to the UK Hydrographic Office’s website and login to their public FTP server.

Figure 2: UK Hydrographic Office public FTP server

Oh no! The Net Worker Alliance knocked Charles de Gaulle Airport offline!!

On to the Net Worker Alliance. This group of pro-Russian hacktivists have also made some funny mistakes of their own. On 29 July and 3 August 2023, the Telegram channel of the group claimed to have launched a DDoS attack to knock the website of Charles de Gaulle airport offline. Not once but twice!

Figure 3: Net Worker Alliance alleges they caused an outage for CDG airport.

The funniest thing is though, that if you go to the website that Net Worker Alliance you’ll quickly realize that this isn’t the CDG airport’s website at all. The website states clearly that it is Not Official and not affiliated with the airport or French government. It is essentially a fan site created for the convenience of tourists and the like. Way to go hackers!

The real CDG airport website is located at https://www.parisaeroport.fr/en/charles-de-gaulle-airport. In March 2023, this site was also DDoSed by Anonymous Sudan, who managed to get the domain right that time.

Figure 4: Anonymous Sudan DDoSes CDG airport website.

No way! Anonymous Sudan stole 30 million Microsoft accounts!!

Despite their impressive abilities to get a URL right, Anonymous Sudan has also made some outlandish claims. While Microsoft did admit that Anonymous Sudan was able to DDoS OneDrive, Outlook, and the Azure Portal offline, they denied that 30 million credentials were stolen.

Figure 5: Anonymous Sudan claiming to have stolen 30 million Microsoft credentials.

This is interesting because while they had finally caught the world’s attention with their frankly unbelievable successful attack on Microsoft’s Cloud services, they still managed to immediately dismantle the credibility they had just earned and continue to look foolish.

WOW! NB65 hacked Kaspersky!!

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has undoubtedly given birth to the largest increase of hacktivist groups emerging in recent years, and perhaps ever. The ‘cyber war’ going on between pro-Russian and pro-Ukrainian hacktivists has been quite entertaining for CTI analysts. Some pro-Ukraine hacktivists pulled off some legendary hacks, like hijacking Russian TV channels to play anti-Putin and anti-War messages or hacking Russian electric vehicle (EV) charging stations to say ‘Putin is a d***head’ on them.

Network Battalion 65 (NB65) is known for attacking Russian companies and performing classical hack-and-leak operations typical for hacktivists. On 9 March 2022, the group hinted that they had compromised Kaspersky’s network and stolen their source code.

Figure 6: NB65 claiming to have hacked Kaspersky.

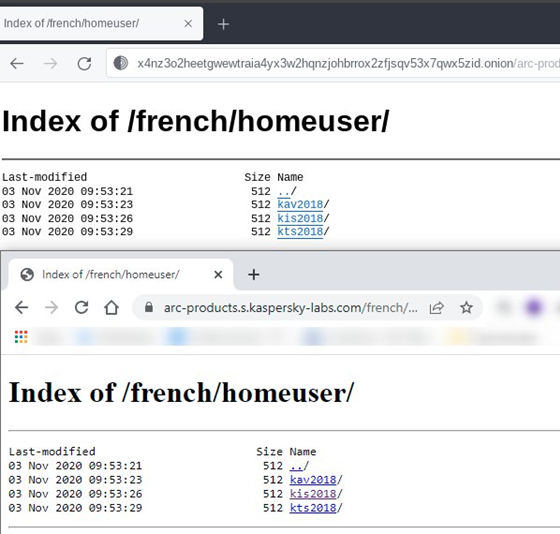

Then on 10 March 2022, the NB65 shared their leak announcement and in it was an Tor URL hosting the “leaked source code” they claimed they stole from Kaspersky.

Figure 7: NB65 data leak announcement for Kaspersky’s code.

Security researchers were quick to point out that the data that was “stolen” by NB65 was simply taken from a publicly accessible directory on Kaspersky’s own website.

Figure 8: NB65 data leak versus Kaspersky’s website.

Once again, another hacktivist exaggerated their claims. This incident particularly caught a lot of attention because it was soon after the February 2022 invasion of Ukraine had just kicked off and various hacktivists were ramping up their attacks on Russian organizations throughout March 2022. These outlandish claims are then shared across social media by researchers who sometimes do little to verify or dispute what these groups allege but amplify and spread their messages anyways.

The State of Hacktivism

From the three case studies laid out above, CTI researchers should continue to remain highly sceptical of any claims put forward by these hacktivist groups. These threat actors are either too technically inept to realize what they’ve “hacked” is nothing of significance (the morons) or they are intentionally exaggerating their claims for clicks and shares to gain influence and notoriety online (the liars).

At the 2022 VirusBulletin conference, Blake Djavaherian shared an excellent paper on The Realities of Hacktivism in the 2020s. It covered (in a lot more depth than this blog) some of the causes of the hacktivist phenomena that we saw in the build-up to the Russia-Ukraine war, as well as the current landscape and its trends. For more information on hacktivist groups in general, I certainly recommend giving it a read if this blog got you interested in the topic. The rabbit hole of hacktivism goes a lot deeper than this!