In 1937, one of the world’s most authoritative art historians, Abraham Bredius, was approached by a lawyer on behalf of a Dutch family estate to inspect a painting of a Christ and the Disciples at Emmaus (pictured above). Bredius dedicated many years of his life studying the artwork of Johannes Vermeer. After inspecting the painting, he wrote that it is not only a Vermeer, but one the greatest pieces Vermeer ever created.

Han Van Meegeren, a mediocre Dutch artist, had in fact forged the work of Vermeer. The above piece was sold during WWII to Nazi Field-Mashal Hermann Goering. Van Meegeren was charged as a Nazi collaborator, but claimed he was national hero. This was because he traded the forgery for 200 original Dutch paintings seized by Goering at the beginning of the war.

To fool Abraham Bredius, the 83 year old art historian whose words were taken as gospel, Van Meegeren had to lay as many clues (or false flags) as he could. This involved making a new painting look like it was on a 17th Century canvas. Not only did the painting have to look like a Vermeer, it also had to fit into the narrative – i.e. the Dutch artist’s life story. Art scholars long suspected that Vermeer went to Italy to study and Van Meegeren’s forgery confirmed this theory. Art historians, connoisseurs, museum directors and unscrupulous dealers were all fooled until Van Meegeren was arrested and charged.

Olympic Destroyer

During the opening ceremony of the 2018 Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang, South Korea, a cyberattack hit the organiser’s systems, causing issues for around 12 hours. The malware used in the attack, dubbed Olympic Destroyer (which is used interchangeably as a name for the group and the malware). Olympic Destroyer was deployed via EternalRomance, one of the NSA exploits leaked by the ShadowBrokers in 2017. It deleted shadow copies, event logs, and then used PsExec and WMI to attempt deeper network infiltration, behaviour that had previously been seen in both NotPetya and BadRabbit, with varying degrees of success.

Following a great deal of speculation on behalf of the cybersecurity community as to which group was responsible for the attack, Cisco Talos published further analysis stating that definitive attribution is simply not possible. Nonetheless, they have listed three groups that are potentially linked to the attack: North Korea’s Lazarus group, and the Chinese-linked APT3 and APT10 groups. These were proposed due to code shared between Olympic Destroyer and malware used in attacks by the aforementioned groups. This attack was a very sophisticated false flag operation from “a skilled and mysterious threat actor” which was deliberately intended to sow confusion amongst security experts.

Security researcher Michael Matonis later scoured over all aspects of the campaign. After weeks of searching, he eventually found clues in the phishing documents, command and control (C&C) servers, and Metadata that could help with attribution to Olympic Destroyer. Matonis noticed that the macros embedded in the malicious Word Documents, used to gain an initial foothold onto the Olympic networks, contained a recognisable pattern of multi-layered obfuscation. Matonis soon deduced the common tool used to create each one of the booby-trapped documents, known as Malicious Macro Generator. This tool is often used by many cybercriminals, but other information such as the files’ Metadata and C&C servers set one cluster of activity apart and tied it to one group. The same attack formula that had been used to target the Winter Olympics was also deployed against Ukrainian LGBT activists and government entities in Ukraine.

More technical details on Matonis’ investigation is available here.

Enter Sandworm

In October 2020, the UK NCSC and US NSA attributed the attack with high confidence. It confirmed that the GRU Unit 74455 (also known as Sandworm) was responsible. Six Russian GRU (military intelligence) officers in connection with global espionage campaigns and destructive malware attacks were charged.

Even with these charges, there is no indication this will prevent the GRU from running these operations. Following the 2018 indictment, against the same GRU Unit 74455, the cyber-spies continued to run their campaigns – albeit with less destructive attacks. Organisations from the infrastructure, energy, government, law enforcement, political, and media sectors must remain vigilant for this threat as it is one of the most advanced, malicious, and persistent in the world.

My review of Andy Greenberg’s Sandworm is available here.

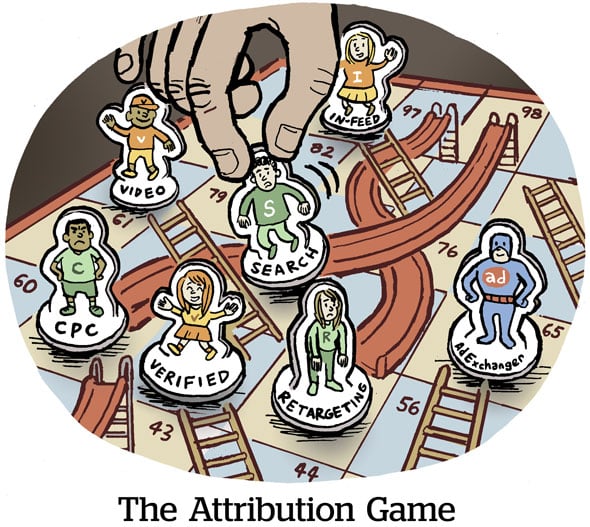

Attribution

What Van Meegeren’s forged Vermeer and the Olympic Destroyer malware have in common is the problem with attribution. Experts at the top of their game had questions asked about their professional analysis. Many may wonder that, if they were wrong about this one thing, what else have they been wrong about in the past? This is the attackers goal – to so doubt amongst the expert communities and to enable plausible deniability.

Robert M. Lee, CEO and co-founder at Dragos, says that threat group attribution is significantly more difficult than people believe. To achieve a high level of confidence in your attribution is incredibly difficult. As a former NSA employee, Lee says that for the agency, a high-confidence level of attribution must include screenshots or camera feeds of the threat actor executing the attack, along with SIGINT and HUMINT evidence. Confident attribution in the private sector is considered low- to moderate-grade attribution for the government.

When talking about national critical infrastructure and cyberattacks upon it, it is especially important that when someone points the blame at one nation state adversary it can potentially be used for diplomatic or even military assessments. Further, it is always worth remembering that nation states can have a variety of intelligence or military agencies. These have their own supply chains and private contractors. They have allies and vendors of their own and they can team up with other countries, at any given point, on operations just like FVEY nations do.

Sources:

http://www.essentialvermeer.com/misc/van_meegeren.html

http://blog.talosintelligence.com/2018/02/olympic-destroyer.html