Earning the title of ‘most dangerous malware in the world’ is no easy feat, especially given the sheer number of cybercriminals and nation-state threat actors vying for that status. However, it’s not a title that can be flaunted openly; achieving it requires both anonymity and the ability to operate with impunity from one’s home base—or at the very least, without the active awareness of local authorities (a rare scenario indeed).

The usual suspects on the world stage of malware development can include Russia, China, North Korea, and Iran. But other groups pop up here and there such as, the US and UK for example, or even Israel, which like to do it with discretion – unlike their counterparts.

At this moment in time, Emotet is widely believed by the security industry to be the most dangerous in the world. First identified in 2014, this Trojan downloader has gripped the security community since its return in September 2019, after a several month long Summer vacation.

Emotet has a complex infection chain which takes advantage of multiple weaknesses in IT systems and exploits problems that have existed for decades, but remain a persistent threat. Emotet utilises a vast botnet, that’s thought to be tiered, composed of thousands of compromised web servers, usually with vulnerable content management systems, like WordPress, that are mostly abandoned which enables the threat actors to maintain control for long periods.

Many organisations have not implemented proper patch management. Many IT systems are left vulnerable for threat actors to exploit and hijack for launching points of their own. Emotet is certainly not the only malware to leverage this fact, but it is possibly the best at it. After the botnet compromises a web server it is likely to secure the way it got in, to maintain persistence. This is how Emotet can grow to such a large size and become a major threat to the public and private sectors around the world.

By using its formidable network of bots as a launching point, Emotet begins its cycle of delivering spam emails, infecting hosts, stealing contact lists, and repeating the process. The stolen emails get added to the spam recipients master list, which by now must be enormous. A Wi-Fi brute-forcing module was also confirmed recently, highlighting the necessity of securing credential access for routers and exercising caution around free public networks.

“Emotet continues to be among the most costly and destructive malware affecting state, local, tribal, and territorial (SLTT) governments, and the private and public sectors.”

– US Computer Emergency Response Team

Emotet infections have cost SLTT governments up to $1 million per incident to remediate, the number of attacks linked to Emotet has not been calculated but it is estimated thousands of businesses have had their daily operations cripple by this malware or the malicious software it delivers, typically the TrickBot banking Trojan, followed by the Ryuk ransomware which forms this ‘triple threat’ of malware.

The Emotet Kill Chain is typically as follows:

What makes Emotet such a widespread threat are its distribution and infection capabilities. It will send hundreds of thousands of malicious emails a day via a network of stolen outbound SMTP accounts. Once it successfully infects a victim’s device it will proceed to scrape the contact list from Outlook. Afterwards the Trojan will send copies of itself in replies to previous conversations the victims may have had with their contacts. This relatively simple mail-man-in-the-middle social engineering approach has made Emotet one of the most prolific vehicles for delivering malware that we have seen in modern times. When receiving an email from a friend or colleague a user automatically feels safe and through these kinds of relationships Emotet can facilitate further infections from entire contact lists, which then get added to the master list and recycled.

The threat actors have also taken care to implement a sophisticated infection chain which is triggered once a victim opens the malicious attachment in its spam emails. The attachments are usually Word or Excel documents, that contain malicious macros which, when enabled, trigger various background VBA and PowerShell scripts that download and install the downloader Trojan to the victim’s device. Each excel document is unique and the code is polymorphic. This means upon each infection the signature of the file is new and unique, this makes traditional antivirus solutions which rely on code – or signature-based detection systems unable to identify an Emotet maldoc (malicious documents) as a threat.

It has been noted by Cisco Talos researchers that to say the attacks are “targeted” would be a stretch, as Emotet continues to infect individuals and organizations all over the world. However, if a person has substantial email ties to a particular organization, when they become infected with Emotet the effects would manifest in the form of increased outbound Emotet email directed at that organization. This is demonstrated by Emotet’s relationship to the .mil (U.S. military), .gov (U.S./state government), and .edu (education institution) top-level domains (TLDs). The botnet operators may believe that this information is the most valuable or can earn huge profits from offering a foothold in these networks to its cybercriminal clientele.

Some of the themes the threat actors leverage in their generic spam emails include banking and finance related invoices or account notices, parcel delivery notifications from FedEx, UPS, DHL, or Amazon, as well as tax returns. Some themes are much more topical and it has been recorded that some spam runs have utilised the popularity of Greta Thunberg, or Edward Snowden’s book, and more recently the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) with fake health warnings.

The first documented version of Emotet was designed to steal bank account details by intercepting internet traffic. This was followed by Emotet version two, which came packaged with several modules, including a money transfer system, malspam module, and a banking module that targeted German and Austrian banks. Then in January 2015, version three of Emotet appeared and contained stealth modifications designed to keep the malware flying under the radar and added Swiss banks to the target list. The Emotet we now know arrived in 2018, as a totally new version of the Emotet Trojan, that had evolved to install other malware to infected machines.

The authors of banking trojans have been continually pushed to combat and overcome evolving financial security measures, such as Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA) and software-based security solutions. This arms-race could well be a motivator for the actors behind Emotet’s distribution having moved to the long-term revenue strategy of leasing out their botnet-as-a-loader platform for other malware like Trickbot or Ryuk.

Emotet is widely-documented to operate as a malware-as-a-service for other cybercriminal organisations. More of than not, the Trickbot banking Trojan is delivered to infected hosts that are under Emotet’s control. Once Trickbot has been downloaded and installed onto the victim’s system it will immediately establish persistence by injecting into running processes and disabling the running antivirus solution, if there is one. What Trickbot specialises in is stealing information for its criminal masters. This can include credentials for access to other systems on the network or for certain web services like Office 365, accounting software, VPN services, password managers, anything of value to the threat actors. Trickbot will check what software is installed on the system and can shift to capture credential access for these services too. It is then designed to move laterally around a network and penetrate deep into the IT infrastructure to reach core and critical systems. It does this via exploiting the EternalBlue vulnerability or via collecting authentication codes with the hacking tool known as Mimikatz, a cybercriminal and nation state threat actor’s favourite. Mimikatz can extract plaintext passwords, hashes, PIN codes, and kerberos tickets from memory to then pass-the-hash, pass-the-ticket or build Golden tickets.

Trickbot is traditionally used in between Emotet and Ryuk ransomware to facilitate the next stage of the attack. On its own, however, Trickbot can render hundreds of accounts compromised and can equal a devastating breach of confidential data belonging to the victim organisation or individual.

Ryuk ransomware is the one that makes a lot of headlines and is the reason for security advisories from the UK NCSC and US CISA for paralysing organisations and demanding a payment to restore operations. This efficient ransomware is able to perform reconnaissance of the network that is infected with Emotet. This enables the attackers to choose which systems to lock or prioritise. Sometimes attackers may wait longer before triggering the encryption algorithm in effort to maximise its reach and impact. The ransomware will enumerate network shares and encrypt the files of all those it can access. Ryuk specifically makes sure that forensic recovery processes are unable to restore any files without of the decryption keys that the threat actors hold onto, or delete, until the victims pay up.

– Prosegur, Spanish security company, represented on 5 continents in 24 countries. The company also has 170,000 employees was shutdown by Ryuk and Emotet (source)

– Tribune publishing newspapers, i.e., Los Angeles Times, Chicago Tribune, Wall Street Journal, and the New York Times (source)

– Ryuk note demands $5 million in ransom from Mexico’s Pemex (source)

– Imperial County, California, the government website and communications system (source)

– Long Island, New York, school district has paid hackers nearly $100,000 to recover data (source)

– Rockville Center, N.Y. School District paid an $88,000 ransom to regain access (source)

– National Veterinary Assosciates hit with ransomware crippiling 400 veterinary hospitals (source)

– Pitney Bowes taken offiline affecting 1.5 million customers worldwide (source)

– Boston’s Committee for Public Counsel Services unable to access its IT network for weeks (source)

– State Government of Louisiana (source)

– Jackson Country, Georgia for more than two weeks and paid $400,000 to cyber-criminals to regain access to their IT systems (source)

– Miami Beach systems taken offline and Ryuk note demands $5 million. Lake City has paid $460,000 and Riviera City $600,000 (source)

– US Coast Guard maritime facility down for more than 30 hours (source)

– Tampa Bay Times attack and Ryuk’s average ransom payment climbs to $780,000 (source)

– T-system, which 40% of US clinics depend on (source)

– TECNOL, ASD Audit, Imperdeco (source)

– Countless others and likely there will be countless more.

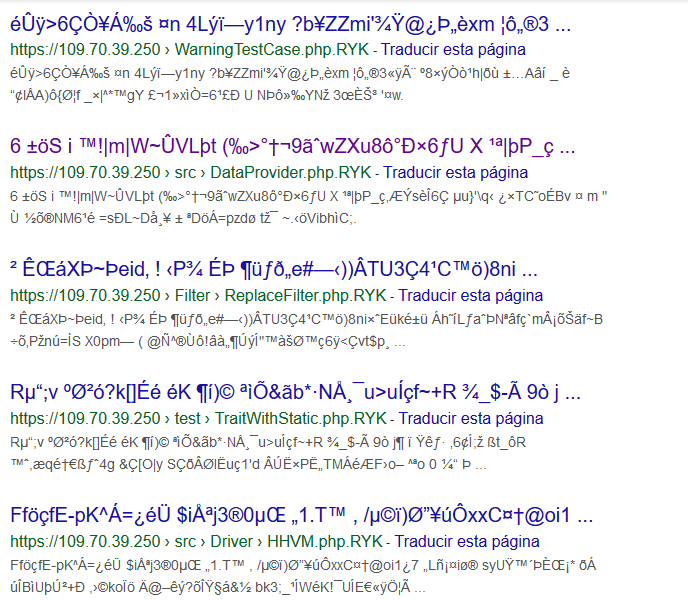

You can see the impact of Ryuk yourself by trying this at home. You can even setup a Google alert to get notified when this file appears on a site’s server, usually after an attack.

In Google, try this to find impacted sites: intitle:”Index of/”+”RyukReadMe.html”

Finding Ryuk-encrypted data from certain companies is sometimes possible by querying public search engines, as shown in the image below:

It has been calculated by TechRadar that victims of Emotet, Trickbot, and Ryuk have had to pay $3,700,000 worth of Bitcoin from 52 known transactions since Emotet’s return in August. However, the damage done by this triple threat of malware may never be fully known due to not all companies disclosing attacks and try to deal with cyber incidents discreetly with expensive incident response firms, the news also still likely to come out eventually.

The botnet’s success is leant to the ruthless efficiency of the threat actors behind it. To keep email templates or recipient and credentials lists fresh and relevant, Emotet must communicate with unavailable recipients, changed credentials, or offline hosts. It will update passwords for usernames as they become available. Persistence is preserved via several methods, such as auto-start registry keys and services. It also uses dynamic link libraries (.dll files) to continuously evolve and update its capabilities, remotely.

Some of Emotet’s advanced detection evasion and anti-analysis techniques include VM-awareness, which means it can detect if it is being run in a specialised environment for malware analysis. By exploiting the left web servers, spread across APAC geographies, the operators can evade attribution attempts due to securing the backdoors they enter through, and is one of the main reasons they have persisted for so long.

Many parts of Emotet’s code is obfuscated, employing time wasting tactics to prevent security researchers from decoding the payloads and to identify where the threat actors are hiding their arsenal. All it takes is for the threat actors to change the keys and the whole process of analysing all that code for one sample is useless for any others. Emotet generally uses the advanced encryption standard (AES), which takes an huge amount of computing power to break, unavailable to security researchers, which again, could be changed instantly and efforts would be wasted. A minor code variation breaks the tools developed by researchers to deobfuscate the malware. Recently, the Japanese computer emergency response team (JP-CERT) recently developed a tool called EmoCheck which was designed to assist system administrators (Sysadmin) to identify any hosts running processes from the in-built wordlist Emotet would masquerade as. However, in less than 24 hours the threat actors altered the list to generate random numbers instead, rescuing the botnet from those pesky security researchers, once again. Emotet has been observed using a subtle market to track which bots are delivering messages on behalf of the actor(s) behind the campaigns. The Message-ID field of each email contains an identified which can be tracked back to the individual bot that sent the message.

The structure of a message ID:

Identifying code [dot] hash (unique code) [@] domain name

Identifier.hash@domain

<20 numeric characters>.<16 hex characters>@<recipient domain>

A more literal example could be:

This message ID would not change linearly or sequentially, but randomly. There are never any identifier overlaps, even across different infections.

Although Emotet has been documented to deliver the Dridex banking Trojan (also known as Bugat or Cridex), which belongs to the cybercriminal master minds at EvilCorp, the threat actors are not believed to be the same and currently there are no substantial connections that have been presented.

If you dig deep enough into the history of Emotet, it used to be known to some vendors as Geodo, its lineage is incredibly convoluted and intertwined with malware such as Cridex as well as the later iterations known as Dridex. Emotet has also been linked by Trend Micro in the past to Dridex via a loader which also delivered Ursnif and BitPaymer. Due to the nature of it being a malware-as-a-service platform it is no surprise that Emotet has dealings and connections with other cybercriminal organisations.

Security researchers which follow the daily IOCs output (such as @cryptolaemus1 and their incredible Pastebin) will know that during the Russian Orthodoc Christmas break the output from Emotet dropped off. The timing does suggest that the operators may be Russian-speaking, also Russian code-snippets have been found in the malware. However, attribution is never easy and could be nothing more than false flags at this stage.

What we do know about the Emotet gang is that they are highly skilled, disciplined, motivated cybercriminals which are well organised and have managed to evade the global security community longer than almost any other group. They are smart, quick, and able to make the exact changes necessary to prevent losing their botnet right before they are enacted. The group certainly watches the news, and monitors the work of security researchers, perhaps this small blog might even crop up on their radar. The size and scale of the spam botnet may also work as an information gathering network, due to the mass compromise of email inboxes, and this may offer a fair amount of intelligence for the group to enact on. Some speculate that Emotet’s hiatus in 2019 may have been because they got wind of a law enforcement agency (LEA) joint task force was being setup to dismantle the botnet – much like its forunners before it, i.e., the Avalanche botnet .

At the moment, no one really knows who is behind the botnet or the Trojan downloader or what their primary objectives are, other than for financial gain. However, much like the EvilCorp crew, the Emotet operators persist with such skill that the country(s) in which they reside – probably Russia – permits them to do so, due to an unwritten agreement that as long as they do not target their own they can attack whoever they want. After an FBI indictment, the Dridex developers were publicly disclosed. This has not deterred them from continuing their attack campaign though, and an indictment of the Emotet/Trickbot/Ryuk group would also unlikely deter them from continuing to make millions of dollars.